Antithrombotic Therapy for the Prevention of Secondary Coronary Artery Disease

The advent of newer antiplatelet agents and oral anticoagulants has allowed new regimens for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. When combination therapy is needed, the bleeding risk is particularly pronounced, and the benefits and risks must be balanced for individual patients.

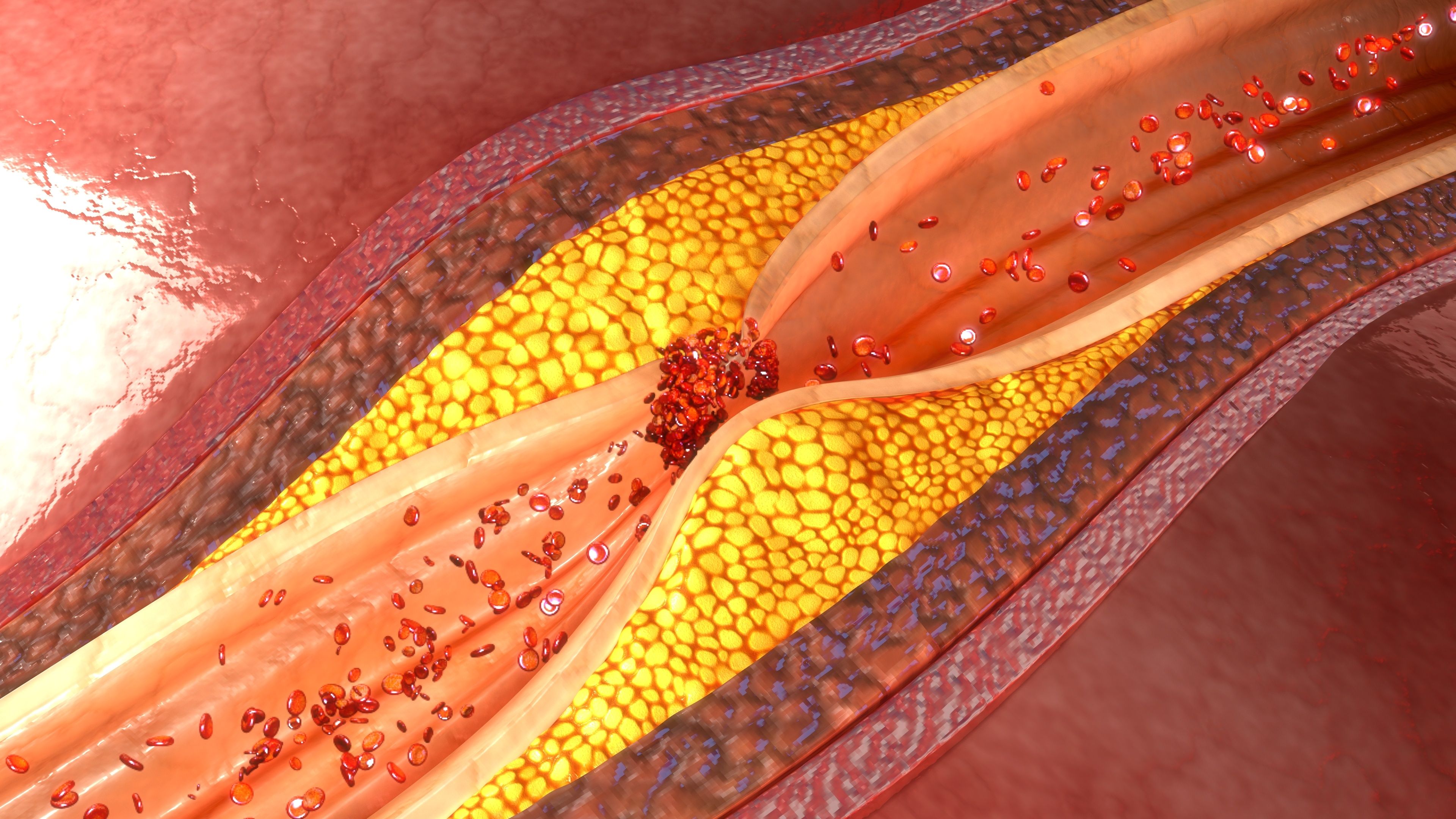

Coronary artery plaque (7ActiveStudio, AdobeStock)

The advent of newer antiplatelet agents and oral anticoagulants has allowed new regimens for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. When combination therapy is needed, the bleeding risk is particularly pronounced, and the benefits and risks must be balanced for individual patients.

In a review published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Freek W.A. Verheugt, et al., discuss antithrombotic strategies for patients with stable coronary artery disease alone, acute coronary syndrome alone, or either condition combined with atrial fibrillation, following either noninvasive or invasive management.

Available Agents

The reviewers begin by reminding readers of the classification of antithrombotic agents: Antiplatelet therapy such as aspirin and the P2Y12 inhibitors clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. And, oral anticoagulants, such as the vitamin K antagonists warfarin and other coumarins. Plus, direct oral anticoagulants, such as the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran and factor Xa blockers rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

Stable Coronary Artery Disease Managed Noninvasively

Aspirin is well-established in international guidelines as the agent of choice for secondary prevention in patient with coronary artery disease. For patients who cannot tolerate aspirin, clopidogrel is similarly safe.

Acute Coronary Syndrome Managed Noninvasively

These patients should receive dual antiplatelet therapy: aspirin loading followed by low-dose aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor. During hospitalization they should also have parenteral anticoagulation. Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily may be added at hospital discharge in stabilized patients.

According to guidelines of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, the P2Y12 inhibitor is mandatory for 12 months after myocardial infarction, unless the patient is at exceptional risk of bleeding. An alternative is to use low-dose rivaroxaban with aspirin.

Stable Coronary Artery Disease with Atrial Fibrillation Managed Noninvasively

Direct oral anticoagulants are as effective as vitamin K antagonists and are much safer with respect to intracranial hemorrhage. These characteristics make them good choices for patients who have both stable coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation.

Oral anticoagulation is definitely necessary when the CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and sex category [female]) stroke score is ≥2.

Although often used, concomitant antiplatelet therapy is not indicated in most patients with stable coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation who were managed noninvasively. The exception is those at exceedingly high thrombotic risk, such as patients with severe diffuse multivessel coronary artery disease.

Stable Coronary Artery Disease Managed Invasively

In patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention, the gold standard for antithrombotic treatment is aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor, usually clopidogrel. Prasugrel or ticagrelor should be considered only in high-risk situations (e.g., complex procedures such as left main coronary artery stenting) and in patients with a history of stent thrombosis during clopidogrel maintenance therapy.

Aspirin is needed lifelong after percutaneous intervention. For patients receiving new-generation drug-eluting stents, the standard duration of the P2Y12 inhibitor is 6 months, but it can be shortened to 3 months in patients at high risk of bleeding (e.g., elderly patients) or even 1 month in patients at very high risk (e.g., those receiving oral anticoagulation).

Conversely, in selected patients at high ischemic risk according to clinical and/or procedural characteristics, the P2Y12 inhibitor can be prolonged beyond 6 months.

Acute Coronary Syndrome Managed Invasively

In this category of patients, the standard of care is to add prasugrel or ticagrelor to aspirin. Both of those agents act more rapidly than clopidogrel, are stronger platelet aggregation inhibitors, and have more predictable response.

The recommended duration of the P2Y12 inhibitor is 12 months, but if there is a high risk of bleeding it can be shortened to 6 months. On the other hand, continuing it for more than 1 year may be suitable for patients with a prior history of myocardial infarction or other risk factors for recurrent ischemic events.

Acute Coronary Syndrome with Atrial Fibrillation Managed Invasively

Patients who have both acute coronary syndrome and atrial fibrillation and were managed invasively need both oral anticoagulation, to prevent stroke, and antiplatelet drugs, to prevent stent thrombosis and other ischemic events. The most common approach is triple therapy: aspirin, clopidogrel, and an oral anticoagulant.

Unfortunately, triple therapy greatly increases the risks of bleeding and mortality. A North American expert consensus paper suggests several new options, especially for elderly patients and those at higher risk of bleeding:

- A vitamin K antagonist plus clopidogrel

- Rivaroxaban 15 mg once daily plus a P2Y12 inhibitor

- Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily

- Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily plus a P2Y12 inhibitor

Dr. Verheugt’s group says these “dual pathway” strategies are especially attractive for patients at high bleeding risk, whereas 1 month of triple therapy may be better for those at high thrombotic risk.

Adding a Vitamin K Antagonist

In patients with either stable or unstable coronary artery disease who do not have atrial fibrillation, a vitamin K antagonist should be added in cases of comorbid venous thromboembolism or when a mechanical heart valve is present. Clinicians should note that this increases the risk of major bleeding.

Take-Home Points

Single or dual antiplatelet therapy is essential for patients with either stable and unstable coronary artery disease, whether management has been invasive or conservative.

Most patients with atrial fibrillation need oral anticoagulation. Direct oral anticoagulants are as effective as vitamin K antagonists and have acceptable bleeding risk profiles for these patients.

When atrial fibrillation complicates coronary artery disease, or vice versa, both antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents are necessary. In patients with acute coronary syndrome and atrial fibrillation who were managed invasively and receive triple therapy, bleeding complications are common, and new regimens have been proposed for reducing the risk. However, until the results of ongoing trials are available, antithrombosis for these patients must be individualized.

REFERENCE:

Verheugt FWA, Ten Berg JM, Storey RF, Cuisset T, Granger CB. Antithrombotic agents: from aspirin to DOACs in coronary artery disease and in atrial fibrillation (part I). J Am Coll Cardiol. Published 2019 Jun 27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.080